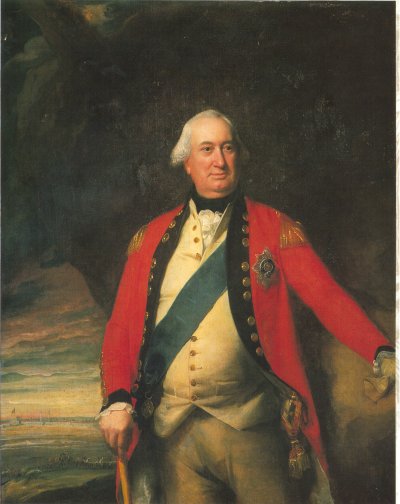

1. Who was Charles Grant?

He was born at Aldourie,

Inverness-shire, Scotland, and went to India in 1767 in a military role. Later through a variety of friends and acquaintances, he rose to the eminent position of superintendent over all of the East India Company's trade in Bengal. Returning to Britain in 1790, Grant became a leading British statesman prior to his death in

Russell Square, London, October 31, 1823.

One of Grant's accomplishments included acquiring a large fortune through silk manufacture in

Malda, India, which resulted in

Governor-General Cornwallis appointing Grant as a member of the East India Company's board of trade in 1787. Later in 1805, Grant became the chairman, Court of Directors, East India Company, and he used his influence to sponsor many chaplains to India, including

Claudius Buchanan and

Henry Martyn.

2. The Context of “Observations”

2.1 In Grant’s politics Elected to Parliament in 1802 from Inverness-shire, Grant served as an MP until failing health forced him to retire in 1818. While in India and later in the British Parliament, Grant exerted much influence in the areas of education, social and public policy, and Christian missions. Grant was a leading figure in the establishment of the Sierra Leone Company (1791), which helped give refuge to freed slaves. Religiously, Grant served as a vice-president of the

British and Foreign Bible Society at its founding in 1804, and crusaded for the

Church Missionary Society and the

Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. Politically, Grant opposed

Governor-General Wellesley's war policies against native Indians, and Grant supported the Parliamentary move to impeach Wellesley.

2.2 In Grant’s religion Other aspects of Grant's social conscience and evangelical identity included his close friendship with various members of the

Clapham Sect, not the least of which was

William Wilberforce, an outspoken abolitionist and evangelical leader. Of greatest significance, Grant sided with Wilberforce in 1813 as the two successfully sought to increase education and Christianity's presence in India alongside the East India Company's commercial interests.

3. The Essay

In 1792, Grant wrote "Observations on the State of Society among the Asiatic Subjects of Great Britain." Although this was a “drainpipe” study of Hindu India this work acquired the status of a Government White Paper. It became a much publicized plea for the toleration of educational and missionary activities in India. Being presented to the Company's directors in 1797 and to the

House of Commons in 1813, the Commons ordered its printing in 1813 within the context of the Charter Renewal. Grant argued that the method for civilizing India in regard to society, morality, and religion would be for the Company to allow Christian missionaries into India along with Christianity's legal establishment. Ironically, Grant's thesis was at odds with the long-held position of the East India Company, which had attempted to prevent Christian missionary work in India. Key figures in the opposition to missionaries in India were Major Scott Waring and the

Rev. Sydney Smith. The essay provides a Christian rationale of Empire

Follow the link::

http://www.wmcarey.edu/carey/grant/75.jpg4. Assessing the Essay

Grant saw Indian society as not only heathen, but also as corrupt and uncivilised. He was appalled by such native customs as exposing the sick, burning lepers and sati. He believed that Britain's duty was not simply to expand its rule in India, and exploit the continent for its commercial interests, but to civilise and Christianise. In effect, this also meant to “Westernise,” though this was not a prime motivation.

The essay urged that education and Christian mission be tolerated in India alongside the East India Company's traditional commercial activity. It argued that India could only be advanced socially and morally by compelling the Company to permit Christian missionaries into India. This view was diametrically opposed to the long-held position of the East India Company that Christian missionary work in India conflicted with its commercial interests and should be prohibited. In 1797, Grant presented his essay to the Company's directors, and then later in 1813, along with the reformer William Wilberforce, successfully to the British parliament.

In this section we are examining somewhat later views of India’s culture, from an English Imperialist perspective, that might be said to be traceable to the influence of Grant et al.

British Education in India

As has been noted by numerous scholars of British rule in India, the physical presence of the British in India was not significant. Yet, for almost two centuries, the British were able to rule two-thirds of the subcontinent directly, and exercise considerable leverage over the Princely States that accounted for the remaining one-third. While the strategy of divide and conquer was used most effectively, an important aspect of British rule in India was the psychological indoctrination of an elite layer within Indian society who were artfully tutored into becoming model British subjects. This English-educated layer of Indian society was craftily encouraged in absorbing values and notions about themselves and their land of birth that would be conducive to the British occupation of India, and furthering British goals of looting India's physical wealth and exploiting it's labour.

In 1835, Thomas Macaulay articulated the goals of British colonial imperialism most succinctly: "We must do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern, a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, words and intellect." As the architect of Colonial Britain's Educational Policy in India, Thomas Macaulay was to set the tone for what educated Indians were going to learn about themselves, their civilization, and their view of Britain and the world around them. An arch-racist, Thomas Macaulay had nothing but scornful disdain for Indian history and civilization. In his infamous minute of 1835, he wrote that he had "never found one among them (speaking of Orientalists, an opposing political faction) who could deny that a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia". "It is, no exaggeration to say, that all the historical information which has been collected from all the books written in Sanskrit language is less valuable than what may be found in the most paltry abridgments used at preparatory schools in England".

As a contrast to such unabashed contempt for Indian civilization, we find glowing references to India in the writings of pre-colonial Europeans quoted by Swami Vivekananda: "All history points to India as the mother of science and art," wrote William Macintosh. "This country was anciently so renowned for knowledge and wisdom that the philosophers of Greece did not disdain to travel thither for their improvement." Pierre Sonnerat, a French naturalist, concurred: "We find among the Indians the vestiges of the most remote antiquity.... We know that all peoples came there to draw the elements of their knowledge.... India, in her splendour, gave religions and laws to all the other peoples; Egypt and Greece owed to her both their fables and their wisdom

But colonial exploitation had created a new imperative for the colonial lords. It could no longer be truthfully acknowledged that India had a rich civilization of its own - that its philosophical and scientific contributions may have influenced European scholars - or helped in shaping the European Renaissance. Britain needed a class of intellectuals meek and docile in their attitude towards the British, but full of hatred towards their fellow citizens. It was thus important to emphasize the negative aspects of the Indian tradition, and obliterate or obscure the positive. Indians were to be taught that they were a deeply conservative and fatalist people - genetically predisposed to irrational superstitions and mystic belief systems. That they had no concept of nation, national feelings or a history. If they had any culture, it had been brought to them by invaders - that they themselves lacked the creative energy to achieve anything by themselves. But the British, on the other hand epitomized modernity - they were the harbingers of all that was rational and scientific in the world. With their unique organizational skills and energetic zeal, they would raise India from the morass of casteism and religious bigotry. These and other such ideas were repeatedly filled in the minds of the young Indians who received instruction in the British schools.

All manner of conscious (and subconscious) British (and European) agents would henceforth embark on a journey to rape and conquer the Indian mind. Within a matter of years, J.N Farquhar (a contemporary of Macaulay) was to write: "The new educational policy of the Government created during these years the modern educated class of India. These are men who think and speak in English habitually, who are proud of their citizenship in the British Empire, who are devoted to English literature, and whose intellectual life has been almost entirely formed by the thought of the West, large numbers of them enter government services, while the rest practice law, medicine or teaching, or take to journalism or business."

Macaulay's strategem could not have yielded greater dividends. Charles E. Trevelyan, brother-in-law of Macaulay, stated: " Familiarly acquainted with us by means of our literature, the Indian youth almost cease to regard us as foreigners. They speak of "great" men with the same enthusiasm as we do. Educated in the same way, interested in the same objects, engaged in the same pursuits with ourselves, they become more English than Hindoos, just as the Roman provincial became more Romans than Gauls or Italians.."

That this was no benign process, but intimately related to British colonial goals was expressed quite candidly by Charles Trevelyan in his testimony before the Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Government of Indian Territories on 23rd June, 1853: "..... the effect of training in European learning is to give an entirely new turn to the native mind. The young men educated in this way cease to strive after independence according to the original Native model, and aim at, improving the institutions of the country according to the English model, with the ultimate result of establishing constitutional self-government. They cease to regard us as enemies and usurpers, and they look upon us as friends and patrons, and powerful beneficent persons, under whose protection the regeneration of their country will gradually be worked out. ....."

Much of the indoctrination of the Indian mind actually took place outside the formal classrooms and through the sale of British literature to the English-educated Indian who developed a voracious appetite for the British novel and British writings on a host of popular subjects. In a speech before the Edinburgh Philosophical Society in 1846, Thomas Babington (1800-1859), shortly to become Baron Macaulay, offered a toast: "To the literature of Britain . . . which has exercised an influence wider than that of our commerce and mightier than that of our arms . . .before the light of which impious and cruel superstitions are fast taking flight on the Banks of the Ganges!"

However, the British were not content to influence Indian thinking just through books written in the English language. Realizing the danger of Indians discovering their real heritage through the medium of Sanskrit, Christian missionaries such as William Carey anticipated the need for British educators to learn Sanskrit and transcribe and interpret Sanskrit texts in a manner compatible with colonial aims. That Carey's aims were thoroughly duplicitous is brought out in this quote cited by Richard Fox Young: "To gain the ear of those who are thus deceived it is necessary for them to believe that the speaker has a superior knowledge of the subject. In these circumstances a knowledge of Sanskrit is valuable. As the person thus misled, perhaps a Brahman, deems this a most important part of knowledge, if the advocate of truth be deficient therein, he labors against the hill; presumption is altogether against him."

In this manner, India's awareness of it's history and culture was manipulated in the hands of colonial ideologues. Domestic and external views of India were shaped by authors whose attitudes towards all things Indian were shaped either by subconscious prejudice or worse by barely concealed racism. For instance, William Carey (who bemoaned how so few Indians had converted to Christianity in spite of his best efforts) had little respect or sympathy for Indian traditions. In one of his letters, he described Indian music as "disgusting", bringing to mind "practices dishonorable to God". Charles Grant, who exercised tremendous influence in colonial evangelical circles, published his "Observations" in 1797 in which he attacked almost every aspect of Indian society and religion, describing Indians as morally depraved, "lacking in truth, honesty and good faith" (p.103). British Governor General Cornwallis asserted "Every native of Hindostan, I verily believe, is corrupt".

Victorian writer and important art critic of his time, John Ruskin dismissed all Indian art with ill-concealed contempt: "..the Indian will not draw a form of nature but an amalgamation of monstrous objects". Adding: "To all facts and forms of nature it wilfuly and resolutely opposes itself; it will not draw a man but an eight armed monster, it will not draw a flower but only a spiral or a zig zag". Others such as George Birdwood (who took some interest in Indian decorative art) nevertheless opined: "...painting and sculpture as fine art did not exist in India."

Several British and European historians attempted to portray India as a society that had made no civilizational progress for several centuries. William Jones asserted that Hindu society had been stationary for so long that "in beholding the Hindus of the present day, we are beholding the Hindus of many ages past". James Mill, author of the three-volume History of British India (1818) essentially concurred with William Jones as did Henry Maine. This view of India, as an essentially unchanging society where there was no intellectual debate, or technological innovation - where a hidebound caste system had existed without challenge or reform - where social mobility or class struggle were unheard of, became especially popular with European scholars and intellectuals of the colonial era.

It allowed influential philosophers such as Hegel to posit ethnocentric and self-serving justifications of colonization. Arguing that Europe was "absolutely the end of universal history", he saw Asia as only the beginning of history, where history soon came to a standstill. "If we had formerly the satisfaction of believing in the antiquity of the Indian wisdom and holding it in respect, we now have ascertained through being acquainted with the great astronomical works of the Indians, the inaccuracy of all figures quoted. Nothing can be more confused, nothing more imperfect than the chronology of the Indians; no people which attained to culture in astronomy, mathematics, etc., is as incapable for history; in it they have neither stability nor coherence." With such distorted views of India, it was a small step to argue that "The British, or rather the East India Company, are the masters of India because it is the fatal destiny of Asian empires to subject themselves to the Europeans."

Hegel's racist consciousness comes out most explicitly in his descriptions of Africans: "It is characteristic of the blacks that their consciousness has not yet even arrived at the intuition of any objectivity, as for example, of God or the law, in which humanity relates to the world and intuits its essence. ...He [the black person] is a human being in the rough."

Such ideas also shaped the views of later German authors such Max Weber famous for his "The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism," (1930) who in his descriptions of Indian religion and philosophy focused exclusively on "material renunciation" and the "world denying character" of Indian philosophical systems, ignoring completely the rich heritage of scientific realism and rational analysis that had in fact imbued much of Indian thought. Weber discounted the existence of any rational doctrines in the East, insisting that: "Neither scientific, artistic, governmental, nor economic evolution has led to the modes of rationalization proper to the Occident." Whether it was ignorance or prejudice that determined his views, such views were not uninfluential, and exemplified the euro-centric undercurrent that pervaded most British and European scholarship of that time.

Naturally, British-educated Indians absorbed and internalized such characterizations of themselves and their past. Amongst those most affected by such diminution of the Indian character was the young Gandhi, who when in South Africa, wished to meet General Smuts and offer the cooperation of the South African Indian population for the Boer war effort. In a conversation with the General, Gandhi appears as just the sort of colonized sycophant the British education system had hoped to create: "General Smuts, sir we Indians would like to strengthen the hands of the government in the war. However, our efforts have been rebuffed. Could you inform us about our vices so we would reform and be better citizens of this land?" to which Gen.Smuts replied: "Mr. Gandhi, we are not afraid of your vices, We are afraid of your virtues". (Although Gandhi eventually went through a slow and very gradual nationalist transformation, in 1914 he campaigned for the British war efforts in World War I, and was one of the last of the national leaders to call for complete independence from British rule.)

British-educated Indians grew up learning about Pythagoras, Archimedes, Galileo and Newton without ever learning about Panini, Aryabhatta, Bhaskar or Bhaskaracharya. The logic and epistemology of the Nyaya Sutras, the rationality of the early Buddhists or the intriguing philosophical systems of the Jains were generally unknown to the them. Neither was there any awareness of the numerous examples of dialectics in nature that are to be found in Indian texts. They may have read Homer or Dickens but not the Panchatantra, the Jataka tales or anything from the Indian epics. Schooled in the aesthetic and literary theories of the West, many felt embarrassed in acknowledging Indian contributions in the arts and literature. What was important to Western civilization was deemed universal, but everything Indian was dismissed as either backward and anachronistic, or at best tolerated as idiosyncratic oddity. Little did the Westernized Indian know what debt "Western Science and Civilization" owed (directly or indirectly) to Indian scientific discoveries and scholarly texts.

Dilip K. Chakrabarti (Colonial Indology) thus summarized the situation: "The model of the Indian past...was foisted on Indians by the hegemonic books written by Western Indologists concerned with language, literature and philosophy who were and perhaps have always been paternalistic at their best and racists at their worst.."

Elaborating on the phenomenon of cultural colonization, Priya Joshi (Culture and Consumption: Fiction, the Reading Public, and the British Novel in Colonial India) writes: "Often, the implementation of a new education system leaves those who are colonized with a lack of identity and a limited sense of their past. The indigenous history and customs once practiced and observed slowly slip away. The colonized become hybrids of two vastly different cultural systems. Colonial education creates a blurring that makes it difficult to differentiate between the new, enforced ideas of the colonizers and the formerly accepted native practices."

Ngugi Wa Thiong'o, (Kenya, Decolonising the Mind), displaying anger toward the isolationist feelings colonial education causes, asserted that the process "...annihilates a peoples belief in their names, in their languages, in their environment, in their heritage of struggle, in their unity, in their capacities and ultimately in themselves. It makes them see their past as one wasteland of non-achievement and it makes them want to distance themselves from that wasteland. It makes them want to identify with that which is furthest removed from themselves".

Strong traces of such thinking continue to infect young Indians, especially those that migrate to the West. Elements of such mental insecurity and alienation also had an impact on the consciousness of the British-educated Indians who participated in the freedom struggle.

In contemporary academic circles, various false theories continue to percolate. While some write as if Indian civilization has made no substantial progress since the Vedic period, for others the clock stopped with Ashoka, or with the "classical age" of the Guptas. Some Islamic scholars have attempted to construct a more positive view of the Islamic reigns in India, but continue to concur with colonial scholars in seeing pre-Islamic India as socially and culturally moribund and technologically backward. A range of scholars persist in basing their studies on views of Indian history that not only concentrate exclusively on its negative traits, but also fail to situate the negative aspects of Indian history in historical context. Few have attempted to make serious and objective comparisons of Indian social institutions and cultural attributes with those of other nations. Often the Indian historical record is unfavorably compared with European achievements that in fact took place many centuries later.

Unable to rise above the colonial paradigms, many post-independence scholars of Indian history and civilization continue to fumble with colonially inspired doctrines that run counter to the emerging historical record. Others more conscious of British distortions and frustrated by the hyper-critical assessment of some Indian scholars, go to the other extreme of presenting the Indian historical record without any critical analysis whatsoever. Some have even attempted to construct artificially hyped views of Indian history where there is little attempt to distinguish myth from fact. Strong communal biases continue to prevail, as do xenophobic rejections of even potentially useful and valid Western constructs, even as Western-imposed hegemonic economic systems and exploitative economic models continue to dominate the Indian economic landscape and often find unquestioning acceptance.

Thus, one of the most difficult tasks facing the Indian subcontinent is to free all scholarship concerning its development and its relationship to the world from the biased formulations and distortions of colonially-influenced authors. At the same time, Indian authors also need to study the West and other civilizations with dispassionate objectivity - eschewing both craven and uncritical admiration and xenophobic skepticism and distrust of the scientific and cultural achievements made by others.

References:

William Carey: On encouraging the cultivation of Sanskrit among the natives of India, 1822 F.I. Quarterly 2-131-37

Thomas Babington (1800-1859),shortly to become Baron Macaulay: Speech before the Edinburgh Philosophical Society in 1846

Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Vintage Books, 1993), p. 168.

Hegel, Samtliche Werke. J. Hoffmeister and F. Meiner, eds. (Hamburg, 1955), appendix 2, p. 243; op cit. Enrique Dussel, The Invention of the Americas (New York: Continuum, 1995), p. 20.

Hegel, Lectures on the Philosophy of World History, Introduction: Reason in History, trans. H. B. Nisbet (Cambridge University Press, 1975), p.138.

From Hegel's Einleitung in die Geschichte der Philosophie (J. Hoffmeister, ed., Hamburg: F. Meiner, 1962), op. cit. Roger-Pol Droit, L'Oubli de L'Inde, Une Amnésie Philosophique, Presses Universitaires de France, 1989, p. 189.

Max Weber, "Soziologie, weltgeschichtliche Analyzen, Politik (Stuttgart: Kroner, 1956), p.340.

Dilip K. Chakrabarti (Cambridge University, England): Colonial Indology - Sociopolitics of the Ancient Indian Past, Munshiram Manoharlal, Delhi, 2000.

Priya Joshi: Culture and Consumption: Fiction, the Reading Public, and the British Novel in Colonial India

Ngugi Wa Thiong'o (Kenya): Decolonising the Mind

M. Abel, (Former Vice-Chancellor, SKD University, Anantapur): Indianisation of Education: Problems and Prospects